Italian Cheese Lore: Big Whisks, Fire Brands and Wild Men

- Pamela Marasco

- Mar 1, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 21, 2025

The collective history and sum of knowledge that influences the making, tasting and traditions of Italian cheese are legendary. The quality of a cheese with a designation of origin is the result of a close link between tradition, knowledge in the raising of heritage animals, feed and forage management, milking and processes of production. Generational traditions and accumulated knowledge is very much a part of the making of Italian cheese.

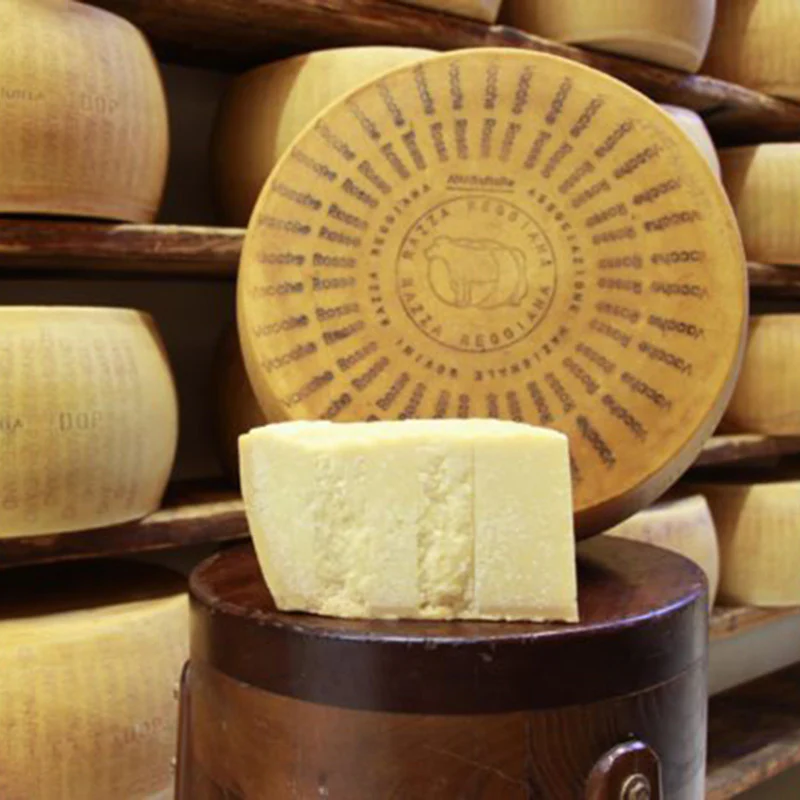

Heritage animals like the Vacche Rosse (Red Cows) of Reggio Emilia whose milk is used to make the finest, oldest and rarest of Parmigiano cheese is a centuries old tradition and the elusive Mozzarella di Bufala made from the milk of the imposing Italian Water Buffalo (Bufala Mediterranea Italiana) is legendary.

The lore and legend of Italian pecorino cheese is often linked to iconic images of sheep grazing in the shadows of Italian cypress between the hilltop villages of Pienza and Montalcino in Tuscany or feasting in the pastures of Sardegna, the rugged Italian island located two hundred miles off the mainland coast.

The landscape of Sardegna is wild and fascinating and the breeds of sheep found equally so. In Arbus, a small town on the southwest coast of the island, to be a black sheep is not a mark of ill repute but refers to a native breed apart from the Sarda Bianca (White Sardinian Sheep). Both breeds produce milk most of which is used to make pecorino sardo cheese.

The choreographed movements of the Parmigiano cheesemakers among the giant copper cauldrons, stirring the curdled milk with the ballon-like spino, a huge whisk used to break down the curd. The word spino comes from the Italian word for “thorn” as they originally used hawthorn branches for this part of the process.

Bell-shaped copper lined cauldrons allow the milk to be heated at the proper temperature and contributes a micro-mineral content that influences the fat in the cheese to create a pleasant flavor note. The predictable size of the cauldron (11 quintals - a historical unit of mass where 1 quintal equals 100 kilograms) allows enough for the production of exactly two cheese wheels.

Using the same tools and rituals with loyalty to tradition and pride in production, Italian cheese makers produce a product that affirms ancient origins and evidence that the cheese of today is made exactly in the same way as it was centuries ago, with the same appearance and the same extraordinary aroma, made in the same places by artisan hands.

With the impressive provenance of Italian cheesemaking it’s no wonder that there should be a legendary Italian pater noster of cheese from the distant past. According to Italian folklore there once was a wild man living in the forests along the Alps and the Apennines described as a master of the cheese trade. Some described him as an Italian version of Bigfoot but more akin to a wilderness cook than a cryptozoological monster. More rational and reasonable, a teacher of sorts. At an ancient encounter near Lucca it is said that the wild man, having taught men to make butter, was about to leave, but the men insisted so much that he stopped to teach them how to make cheese. He started to leave, but once again was pressed to continue and so explained how to produce ricotta. He would often appear unexpectedly to help and correct the local cheese makers yet gained little respect for his efforts. European urbanization drove these bands of wild men (in some cases women) to extinction. They survive in regional paintings, carvings and iconographic representations and a subjects of inspiration at local trattorie.

Ancient legends kept the story of l’uomo selvantico alive and the lore of the wild men of the forests created a whimsical mythology. When Alfonso d’Este married Lucrezia Borgia, a dance was staged at the wedding banquet with performers as wild men carrying horns of plenty. The wild man legend so captured Leonardo da Vinci‘s imagination that in the planning of a nuptial pageant for the Milanese Sforza family he mentions putting footman in their costumes as ‘omini salvatichi’ or wild men. Some say the hypertrichotic selvani still exist. Periodic sightings describe footprints similar in shape to those of humans that sank into the ground to fifteen centimeters. In December 1996 a Swiss music producer reported that he saw in the woods of Ventimiglia in Northern Italy “a gigantic creature that looked like a cross between a primitive man and a gorilla covered with hair with the face of an elderly person”. Hopefully on his way to make cheese.

Our visit to the "caseificio" at Consorzio Vacche Rosse Via F.lli Rosselli 41/2 – 42123

Reggio Emilia (RE)

Comments